A Revolutionary Impulse:

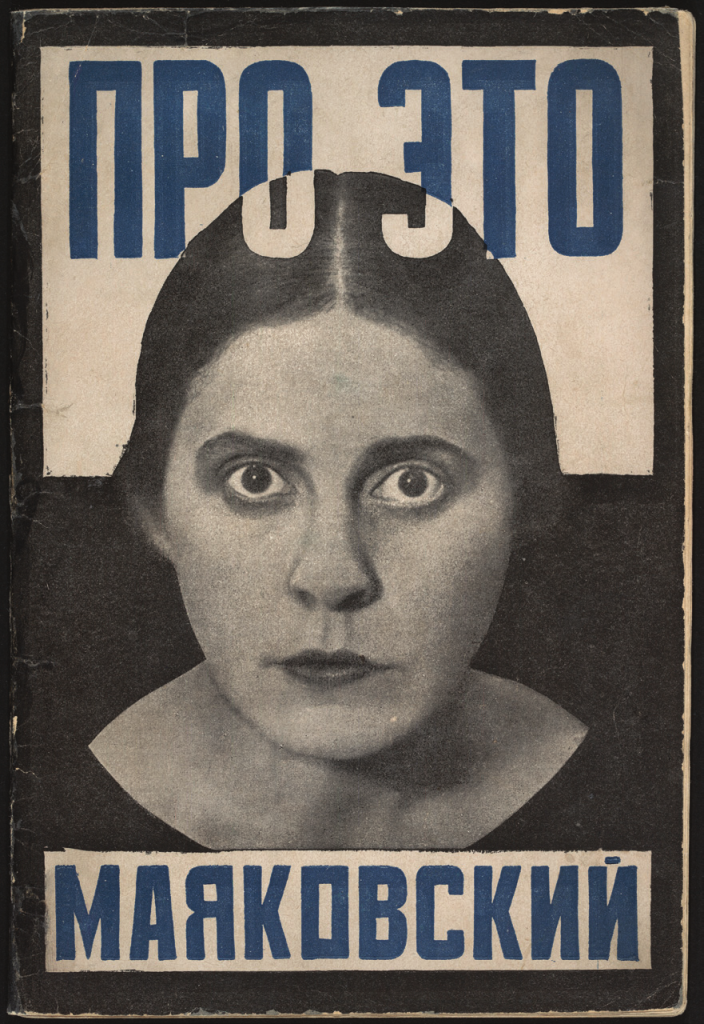

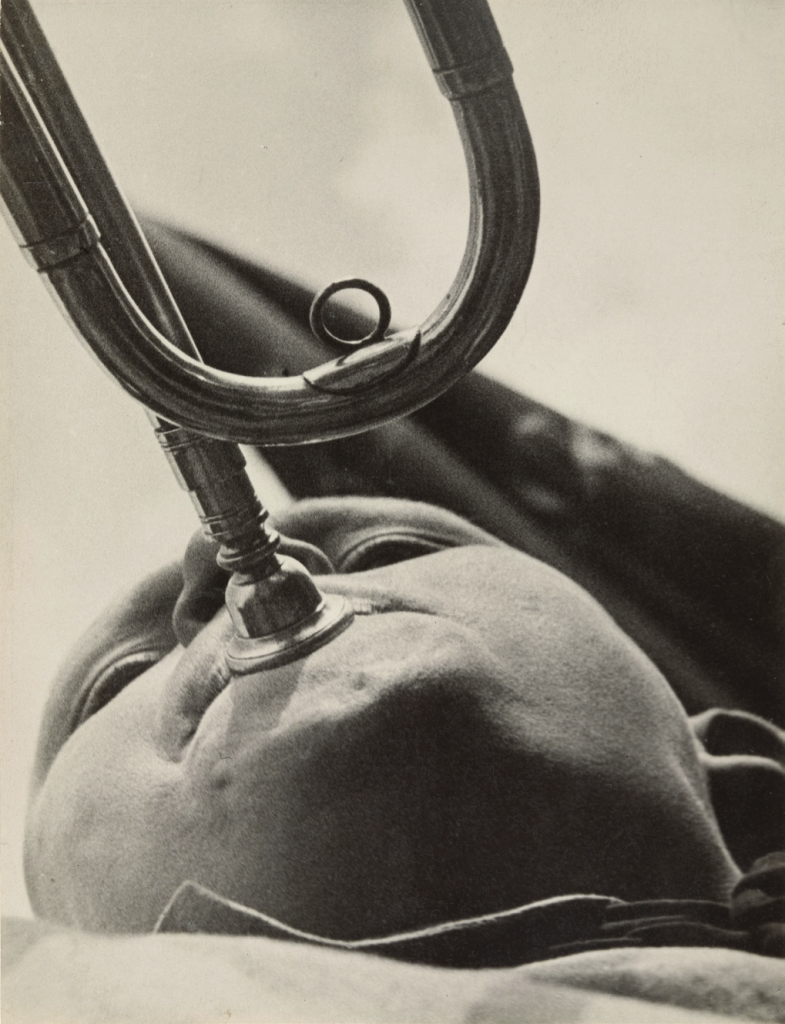

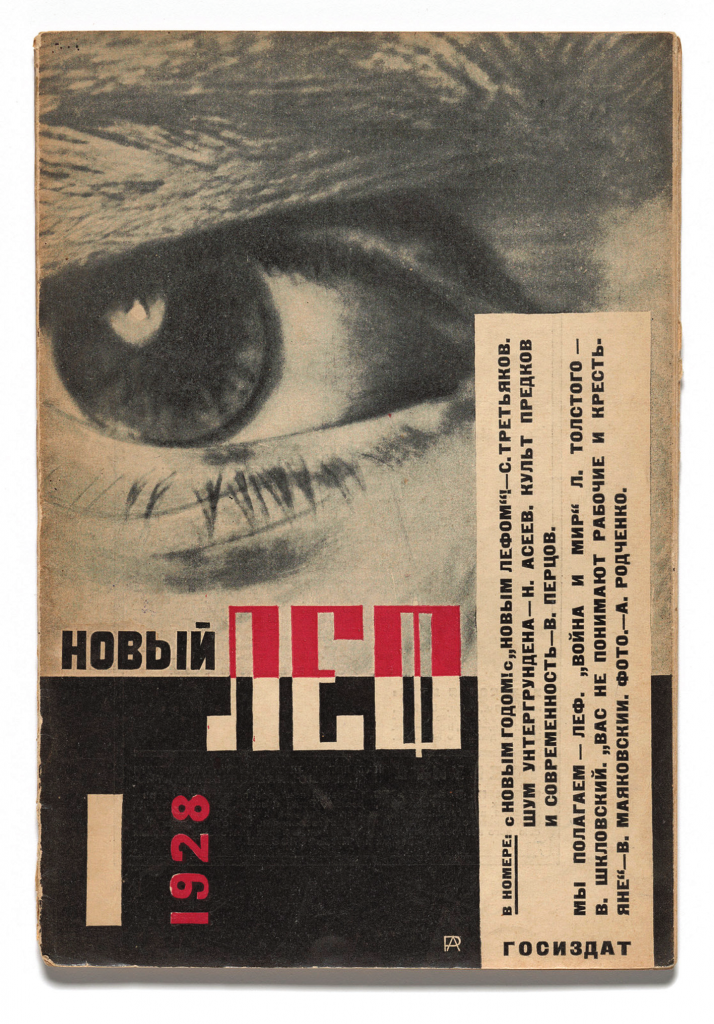

The Rise of the Russian Avant-GardeThe Museum of Modern Art presents A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde, an exhibition that brings together 260 works from MoMA’s collection, tracing the arc of a period of artistic innovation between 1912 and 1935. Planned in anticipation of the centennial year of the 1917 Russian Revolution, the exhibition highlights breakthrough developments in the conception of Suprematism and Constructivism, as well as in avant-garde poetry, theater, photography, and film, by such figures as Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Lyubov Popova, Alexandr Rodchenko, Olga Rozanova, Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg, and Dziga Vertov, among others.

The exhibition features a rich cross-section of works across several mediums-opening with displays of pioneering non-objective paintings, prints, and drawings from the years leading up to and immediately following the Revolution, followed by a suite of galleries featuring photography, film, graphic design, and utilitarian objects, a transition that reflects the shift of avant-garde production in the 1920s. Made in response to changing social and political conditions, these works probe and suggest the myriad ways that a revolution can manifest itself in an object.

In Russia in the early twentieth century, farreaching artistic innovation and intense social and political turmoil were inextricably intertwined. During the early 1910s, under the tsarist autocracy that had ruled for three centuries, avant-garde artists sought to overthrow entrenched academic conventions by experimenting with complex ideas that would transform the course of modernist visual culture. In 1915, as World War I raged, an abstract mode of painting called Suprematism abandoned all concrete pictorial references, while the “transrational” poetic form zaum explored the insufficiency of language to describe reality, freeing letters and words from specific meanings, emphasizing instead their aural and visual qualities. With the October Revolution of 1917, Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik party took command and instituted Marxist policies. Enthusiastic about the new government’s socialist goals, avant-garde artists put individual expression aside and developed a structured abstract language called Constructivism that they hoped could be embraced by the masses.

Constructivists rejected easel painting in favor of practical objects like ceramics, posters, and logos. They adopted mechanical reproduction in place of the artist’s unique hand. And they embraced film, design, theater, and photography, which, in their potential to reach mass audiences, embodied the Revolution’s initial democratic tenets. By the late 1920s, the government, now headed by Joseph Stalin, had placed restrictions on all aspects of life, including the arts, and was commissioning artists to produce propagandistic books, posters, and magazines touting Soviet achievement. Utopian goals were forced aside, and, in the early 1930s, Socialist Realism was decreed the sole sanctioned style of art, abruptly ending a period of pioneering experimentation. This exhibition spans the years 1912 to 1935 with works drawn entirely from the collection of The Museum of Modern Art. Conceived in response to changing socio-political and artistic conditions, these works probe the many ways that an object can be revolutionary.

The international Art Magazine

The international Art Magazine